Anthropomorphism is “considered as the attribution of human characteristics and the qualities to non-human beings, objects, or natural phenomena” (Atkinson 2013). Anthropomorphism is often used on animals, particularly those in children’s films, books and cartoons. However is it safe that we show children human qualities in animals? Animals such as bears or lions that we portray as friendly, when there true nature is often the opposite and they as seen as dangerous.

I’ve always remembered children’s films with animals that have human characteristics; the most common being that they can talk, and I’ve never wondered why we give animals human qualities before. According to Ann Casano, the main reason to give human qualities is that “it make’s the unfamiliar appear more familiar to a reader or spectator”. This is a viable reason, as once we give animal characters human characteristics; the audience is then able to connect with the character.

Scientists have started to warn that anthropomorphism can be dangerous.

“An unconscious belief that bears, horses and dolphins possess human desires and thoughts wrapped up in odd costumes can be detrimental for children, some psychologists have argued” (Milman 2016).

In fact, when psychologist Patricia Ganea conducted an experiment on children ages three to five years in which children were given information about animals in two different ways. First factual information about animals and then in an anthropomorphised fantasy way. Ganea found that the children “were likely to attribute human characteristics to other animals and were less likely to retain factual information about them when told they lived lives as furry humans” (Milman 2016).

The effect of anthropomorphism is that we start to believe and an inaccurate understanding of the natural world and what happens in it. This could be dangerous because it alters the way we might interact with certain animals, particularly wild animals. Certain behaviours such as adopting a wild animal as a pet can be harmful for both the animal and the owners. This stems from the notion that wild animals do not belong in captivity or away from their natural habitat as they changes the way they behave.

Movies such as Finding Nemo (2003) see a shark becoming a vegetarian. Or Yogi bear as a friendly intelligent and not dangerous bear. We give these animals behaviours we want to portray to our children. Simba from The Lion King (1994) was brave and went on a journey of self-actualisation. Many are starting to believe that is it dangerous.

I personally don’t believe that giving animals human characteristics is dangerous, but I do however believe there is a time and a place for it. If in children’s animations we choose to portray anthropomorphised animals, we need to explain to our children that this is not how animals actually behave, that you couldn’t just walk up to a bear in their natural habitat and expect a hug. But if our children understand the truth, watching a film about a certain clown fish finding its way home isn’t dangerous for kids, and can teach them certain lessons. Like most of the media that we watch, we need to understand that we are seeing what someone wants us to see, there’s usually a whole other viewpoint.

Talk soon,

Tash xx

References:

Atkinson, N, ‘The Use of Anthropomorphism in the Animation of Animals: What all animators should know’, NCCA, viewed 26 March 2016 <https://ncca.bournemouth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/NAtkinsonInnovations.pdf>.

Other references are hyperlinked.

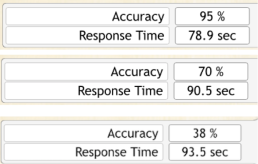

e background and my brother did his in his room also in silence. Now taking a look at these results, can you guess who was in silence and who was watching TV? That’s right, my mum only got a 38% accuracy rating, whereas both my bother and I had higher results. What was interesting is that I received the highest accuracy of 95% meaning that my attention is pretty well, but my response time was lower then both my mothers and brothers. I believe this is due to my tendency to want to get things right so I took my time. Once the game was conducted the first time, we each did it again but swapped the place we completed the task, my brother and I were in the TV room, my mum in the silence of another room. What we found was that my brothers and I’s result only dropped slightly, whereas my mums went up to over 70%. Could this mean that as we get older distractions such as televisions take a larger tool than expected?

e background and my brother did his in his room also in silence. Now taking a look at these results, can you guess who was in silence and who was watching TV? That’s right, my mum only got a 38% accuracy rating, whereas both my bother and I had higher results. What was interesting is that I received the highest accuracy of 95% meaning that my attention is pretty well, but my response time was lower then both my mothers and brothers. I believe this is due to my tendency to want to get things right so I took my time. Once the game was conducted the first time, we each did it again but swapped the place we completed the task, my brother and I were in the TV room, my mum in the silence of another room. What we found was that my brothers and I’s result only dropped slightly, whereas my mums went up to over 70%. Could this mean that as we get older distractions such as televisions take a larger tool than expected?

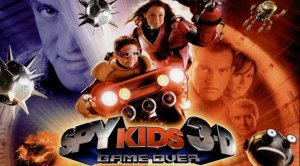

every now and then. Instead of this ‘Netflix and chill’ that has taken over the Internet it use to be ‘how about dinner and a movie this weekend?’ Numbers will most likely drop, but I believe that people will still be attending cinemas for years to come, especially with the introduction of new technologies. I remember watching my first 3D movie ‘Spy Kids’ and I’m sure in years to come I might be remembering the first movie I watched where I could smell the food on screen.

every now and then. Instead of this ‘Netflix and chill’ that has taken over the Internet it use to be ‘how about dinner and a movie this weekend?’ Numbers will most likely drop, but I believe that people will still be attending cinemas for years to come, especially with the introduction of new technologies. I remember watching my first 3D movie ‘Spy Kids’ and I’m sure in years to come I might be remembering the first movie I watched where I could smell the food on screen.